What is a solid-state battery? What is in-situ polymerization technology and what opportunities and challenges does it bring?

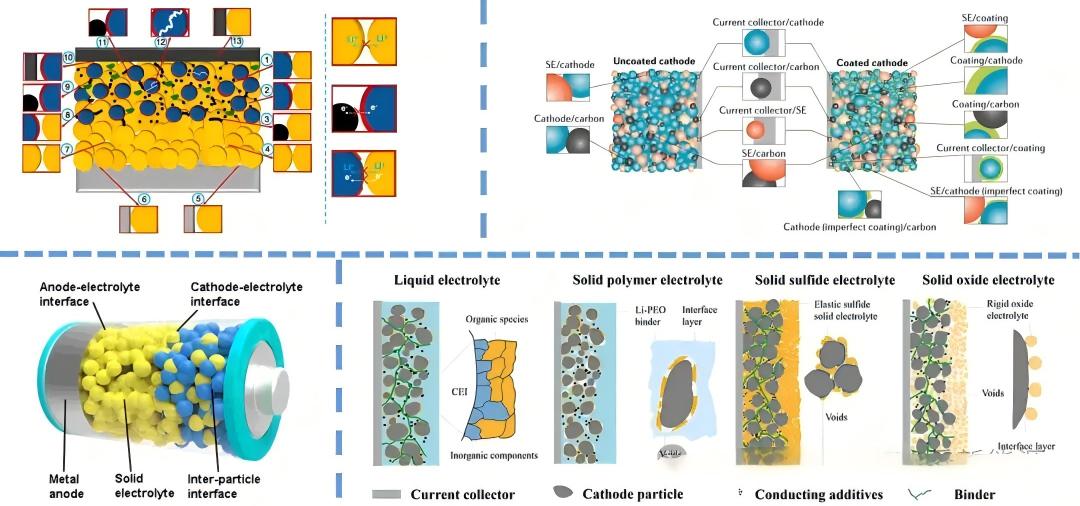

Solid-state batteries have long been regarded as the holy grail of next-generation battery technology due to their theoretical advantages of high safety and high energy density. However, on the road from the laboratory to the market, a core bottleneck has always been difficult to overcome: the solid-solid interface problem between the solid electrolyte and the electrode. The rigid inorganic electrolyte and the electrode are difficult to form a perfect physical contact, resulting in a huge interface impedance, which seriously affects the transmission efficiency of lithium ions and the cycle performance of the battery.

Today, standing at the end of 2025, we deeply analyze a key technology hailed as potentially solving the "last mile" problem of mass production of solid-state batteries - in-situ polymerization technology.

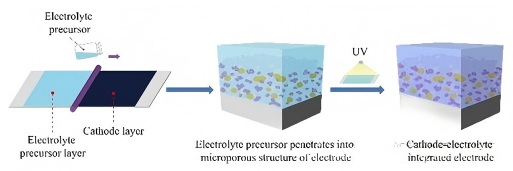

To overcome the challenge of solid-solid interfaces, scientists have proposed a ingenious solution: instead of pre-preparing solid electrolyte membranes, they inject liquid "precursors" into the battery and then solidify them in situ through specific methods (such as heating or light exposure) to form a solid electrolyte network that seamlessly adheres to the electrodes. This is the core idea of in-situ polymerization technology.

This article will provide a comprehensive interpretation of this cutting-edge technology route from multiple dimensions, including technical principles, core materials, performance regulation, industrial status quo, and key enterprises.

●In-situ polymerization: A revolution from "coating" to "pouring"●

The preparation of traditional solid-state batteries is similar to "applying a film" to a mobile phone. First, polymers or inorganic powders need to be processed through complex techniques (such as casting and hot pressing) to form an independent solid electrolyte membrane. Then, this membrane is laminated and pressed together with the positive and negative electrodes. This "applying a film" process cannot guarantee 100% tight contact between the membrane and the electrodes. There will always be tiny gaps, which become "speed bumps" hindering the transmission of lithium ions.

The in-situ polymerization technology represents a revolutionary shift from "coating" to "in-situ pouring". Its basic process is:

1.Prepare the precursor solution: Mix the polymerizable monomers, lithium salts, initiators, and other functional additives to form a low-viscosity liquid mixture.

2. Battery injection: Pour this precursor solution into the already assembled positive and negative electrode coils or laminations. The liquid can thoroughly penetrate the electrode surface and porous structure, achieving an atomic-level tight contact.

3. In-situ polymerization curing: By applying heat or ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation, the initiator is activated, triggering the polymerization and cross-linking reactions of the monomers. Eventually, a solid-state polymer electrolyte with a three-dimensional network structure is formed within the battery.

This "in-situ casting" method fundamentally resolves the contact problem at the solid-solid interface, significantly reducing the interface impedance, thereby enhancing the rate performance and cycle stability of the battery.

●Key Materials: Selection of Monomers and Polymerization Principles●

The success or failure of in-situ polymerization technology hinges on the core component of the precursor liquid - the polymerizable monomers. These monomers need to have good fluidity in the liquid state and good wettability towards the electrodes, and upon polymerization, form a polymer network that possesses both high ionic conductivity and excellent mechanical properties.

Currently, the main monomer material systems include the following categories:

1.Acrylates

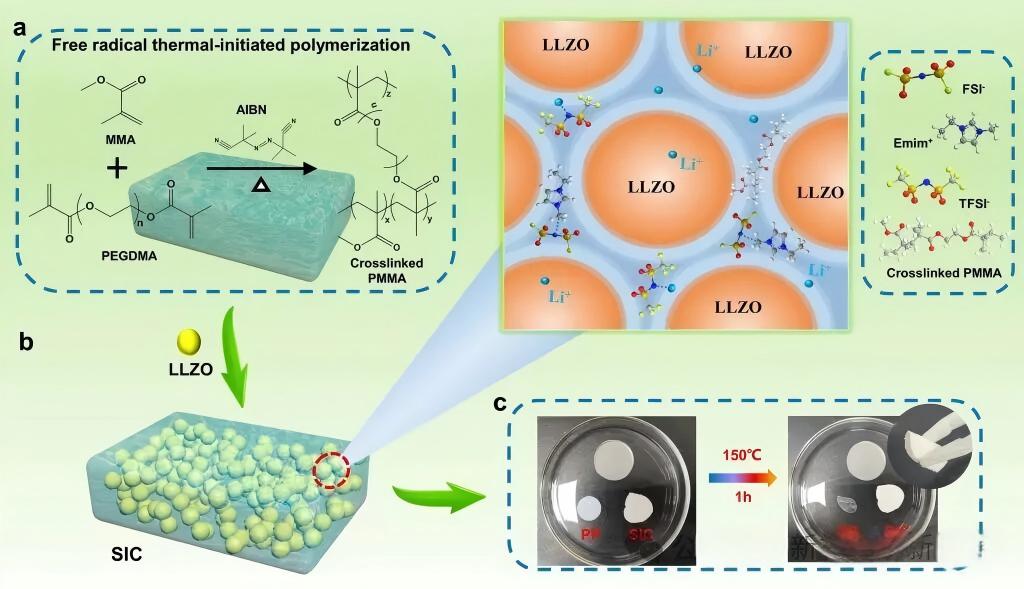

This is currently the most widely studied and most mature type of monomer. They usually contain two or more acrylate functional groups (C=C-COO-), and can rapidly form a cross-linked network through free radical polymerization.

Representative monomers: trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA), ethoxylated trimethylolpropane triacrylate (ETPTA), polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA), etc. These multi-functional monomers can be used as crosslinking agents to form stable three-dimensional networks.

Polymerization principle: Free radical polymerization.

Initiation method: Usually, thermal initiation or light initiation is adopted. Thermal initiators such as azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) and benzoyl peroxide (BPO) decompose at a certain temperature (typically 60-80°C) to produce free radicals. Light initiators generate free radicals under the irradiation of specific wavelengths of ultraviolet light, achieving rapid curing.

Reaction process: Free radicals attack the double bond of acrylic acid, break the double bond and form new free radicals, initiating a chain reaction. Due to the presence of multiple double bonds in the monomer, cross-linking occurs during the polymerization process, forming a three-dimensional network structure, thus transforming from a liquid state to a solid state.

Advantages and Disadvantages: Fast reaction speed, mild polymerization conditions, and wide availability of raw materials. However, during the polymerization process, there may be volume contraction, and some acrylic acid monomers may undergo side reactions with the lithium metal anode.

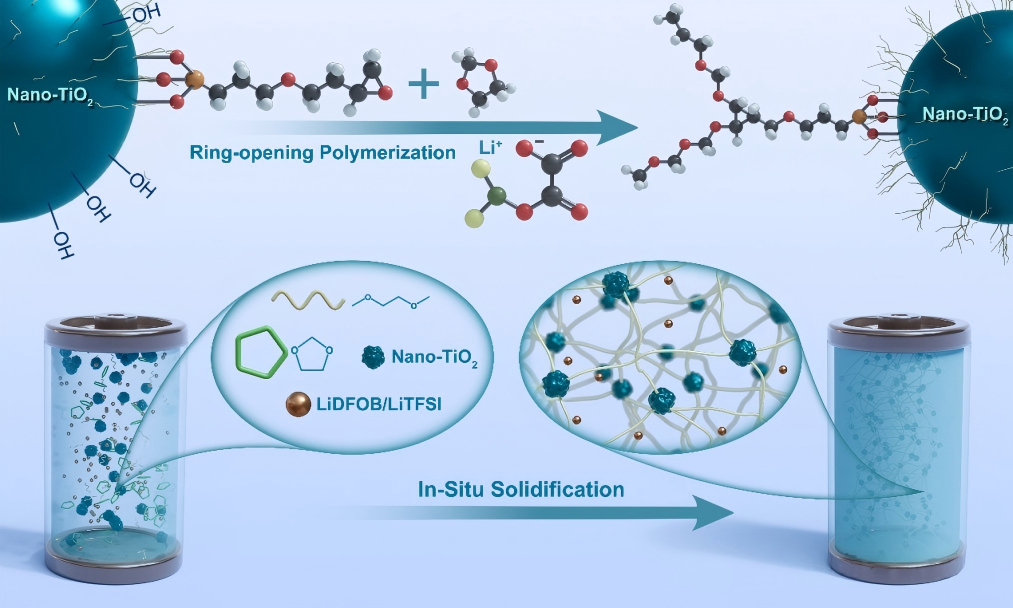

2. (Ring) Ethers (Ethers / Cyclic Ethers)

The polyether segments (especially polyethylene oxide PEO) have excellent complexation and transport capabilities for lithium ions, and are the classic framework for constructing solid-state electrolytes.

Representative monomers: Monomers containing epoxy groups, such as trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTGE), or monomers modified based on polyethylene glycol (PEG). 1,3-Dioxolane (DOL) is also commonly used as a reactive solvent or copolymer monomer.

Polymerization principle: Cationic ring-opening polymerization. Initiation method: Usually, a Lewis acid (such as BF₃·OEt₂) is used as the initiator. In some systems, the lithium salt itself (such as LiTFSI) can also initiate or promote the polymerization under specific conditions.

Reaction process: The initiator attacks the oxygen atom of the cyclic ether, causing it to open up and form an active center with positive charge. This active center then continues to attack other cyclic ether monomers, achieving chain growth.

Advantages and disadvantages: The formed polyether network is very favorable for lithium ion conductivity, but the cationic polymerization reaction is usually very sensitive to water and impurities, and process control requirements are higher.

3. Other single-component systems

Apart from the two major mainstream systems mentioned above, researchers are also exploring other types of monomers in the hope of achieving even better overall performance:

Nitriles: For example, acrylonitrile (AN), whose polymer polyacrylonitrile (PAN) has a high dielectric constant, is conducive to the dissociation of lithium salts, but it has poor mechanical properties and often requires modification.

Carbonates: For instance, vinyl carbonate (VC) can not only serve as a film-forming additive but also participate in polymerization, enhancing the interface stability with the electrode.

Siloxanes: The polysiloxane segments have extremely low glass transition temperatures and excellent flexibility. Incorporating them into the polymer network is expected to enhance the ionic conductivity of the electrolyte at low temperatures.

However, simple polymer electrolytes often fail to simultaneously meet the requirements of high ionic conductivity and high mechanical strength. Therefore, in the in-situ polymerization technique, the strategies of "mixing and matching" and "ingredient addition" for performance regulation are indispensable.

1. "Mixing with non-electrolyte": Constructing organic-inorganic composite electrolytes

This is one of the most popular and promising directions at present. An inorganic solid-state electrolyte (such as oxides, sulfides, halides) powder with high ionic conductivity serves as the "framework", and the polymer formed in situ is used as the "flesh" to fill in between, resulting in an organic-inorganic composite solid-state electrolyte (CSEs).

<p style="text-align:center"

Compared with oxides (such as LLZO, LAGP): Oxide electrolytes (such as Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂) have high mechanical strength and good chemical stability, but they are inherently hard and brittle, resulting in poor contact with the electrodes. Through in-situ polymerization, flexible polymers can fill the gaps between LLZO particles and encapsulate the LLZO particles, forming a continuous lithium-ion transport network, while significantly improving interface contact and reducing interface impedance.

Compared with sulfides (such as Li₆PS₅Cl, Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂): Sulfide electrolytes have ion conductivity comparable to that of liquid electrolytes, but they have poor air stability and are prone to react with water to form toxic H₂S gas, and have a high reaction activity with the lithium metal interface. The dense polymer layer formed in situ can play the role of a physical barrier and protective layer, improving the stability of sulfide electrolytes and enhancing their processing performance.

Compared with halides (such as Li₃YCl₆): Halide electrolytes have emerged as a new star in recent years, featuring high conductivity and good electrochemical stability. By combining them with in-situ polymerization technology, it is expected to further optimize the interface issue between them and the electrodes (especially the negative electrode), and leverage their advantages in high voltage stability.

2. "Adding Materials" - Selection and Dosage of Lithium Salts and Plasticizers

Selection and dosage of lithium salts: Lithium salts are the source of free-moving lithium ions in the electrolyte, and their types and concentrations are of crucial importance.

Types: Common lithium salts include bis-trifluoromethanesulfonylimide lithium (LiTFSI), bis-fluorosulfonylimide lithium (LiFSI), tetrafluoroborate lithium (LiBF₄), etc. When choosing, factors such as their dissociation ability, compatibility with the polymer matrix, and electrochemical stability should be considered. LiTFSI and LiFSI are favored because their anions have large volume and good charge delocalization, which can act as a "plasticizer", reducing the crystallinity of the polymer and facilitating ion transport.

Dosage: The concentration of lithium salt is not necessarily the higher the better. If the concentration is too low, the number of charge carriers will be insufficient; if it is too high, it will cause ion association to form ion pairs, or it may hinder the movement of polymer chain segments, thereby leading to a decrease in ionic conductivity. There is usually an optimal molar ratio range. For example, in some systems, the molar ratio of lithium salt to the polymer repeat units can be between 0.125 and 0.25 to achieve better conductivity.

Addition of plasticizers/ electrolytes: To further enhance the room-temperature ionic conductivity, researchers often add a small amount of liquid plasticizers to the precursor, such as carbonate solvents (EC/PC) or ionic liquids (ILs). This results in the final formed electrolyte being in a state between solid and liquid, known as gel polymer electrolyte or quasi-solid electrolyte. This approach can significantly increase the conductivity to the order of 10⁻³ S/cm, but it sacrifices some safety and is an important transitional solution towards all-solid-state batteries.